A loading screen appears; an 8-bit avatar decides to embark on one of two very different roads: choosing whether to dance over the specifics, or more courageously kill the vibe.

I don’t look to great work for inspiration or escape so much as for an ultimate solution. I turn to the poets and the craftspeople and the entrepreneurs and the athletes and the artists and the philosophers looking to fashion a master key. One that when turned in my most difficult locks could open the doors to a life without the pains or ills that are woven into my routine.

But as I age, and my days become more practice than theory, I slowly accept that a level of strife accompanies those who seek out life: it is a meek and clingy companion willing to keep a distance, at times, but refusing complete abandonment. The self that sleeps and stretches and weeps and struts and loves must also grieve.

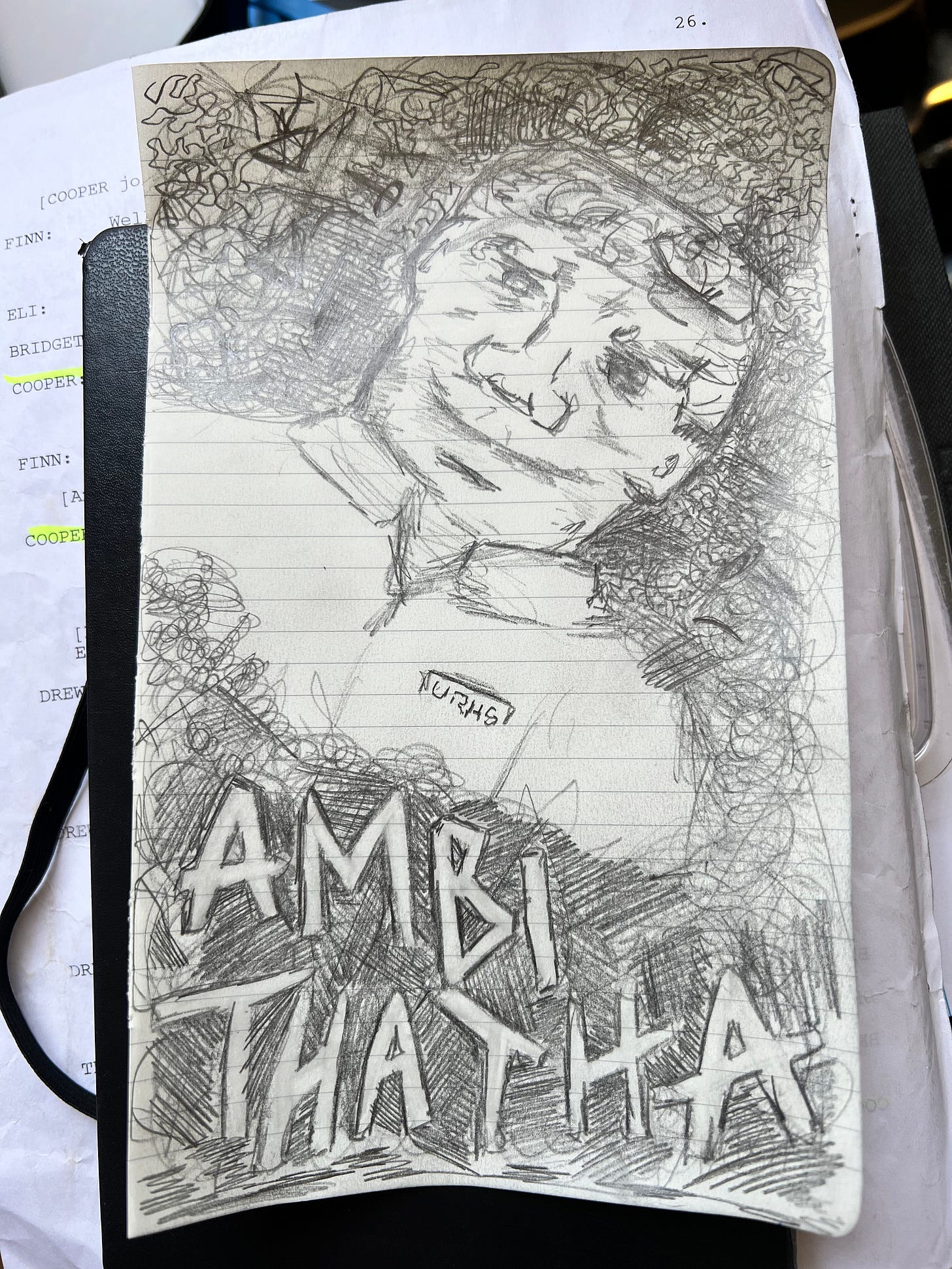

I can’t relate to the warriors who wield their swords with unwavering grip. My hands are wet with sweat even when faced with the weight of a delicate pen. Nevertheless, I have attempted to do justice to the story of my summer over this trilogy, and here begins the final part: In loving memory of…

I’ve been back in LA for a little over a week, and I have a new party trick. I take out my Sky Guide app while at the bar or the club or while with a friend in my front lawn at night, and share with others a search of the sky for the stars we cannot see. I track constellations; I watch the moon make haste across the heavens and wonder if she is running from or to.

Near the end of June, before Thatha passed, my friends and I had all individually seen the movie Past Lives, and had different takes on the ending. My good friend Yamini and I were distinctly opposed in our interpretations, and while there is no end to the number of ways that our vastly different identities and experiences could have informed our differing conclusions on an intentionally ambiguous piece of art, as is typical in LA, we deferred to the stars. Her Venus is in Taurus and mine in Leo, and thus our difference is no fault of our own.

After my grandfather’s funeral, I was instructed on the guidelines for our twelve days of mourning. We were not to leave the house, and no one was to come in, unless the 9 year old twins’ friends wanted to come over, or the men of the house wanted to play badminton at the new indoor courts. We cannot eat onions or garlic, unless you do by accident; and you must rotate between only three sets of clothes, unless you get kind of sweaty earlier in the day than you had expected. Food must be prepared for religious rites on days 10, 12, and 13 of the mourning period, or maybe day 11 and not 12- maybe days 11 AND 12- meaning either 12 days from when Thatha died or maybe 12 days from when he was cremated, which are two days that are farther apart than they maybe should be because the morticians had July 4th weekend off. Some rules that had no uncertainty were that a flame by Thatha’s portrait had to stay lit for all twelve days, and every night, he was given a little bowl of dessert.

Those participating in these twelve days of ritual, thus sharing space at all times, included:

One pair of 9 year olds girls born on 9/11/2013. They understand why their class takes a moment of silence on their birthday and they have made peace with it.

One 13 year old only boy who flew with his X-Box and is much smarter than the 9 year olds, he knows it; or he knows that he hopes that he knows it.

Another pair of twins turned freshly 24, of which I am included.

Six Gen-Xers, of which details will be spared because I don’t think they’d like that.

One surprisingly political and recently widowed grandmother.

There was no shortage of reminders of my grandfather’s presence across the home that he spent his last years in. Yet, the week after he died, even within the borders of behavior set by our loosely yet intentionally followed religious rites, I could think of almost anything but his memory.

Claustrophobically compacted in a shack of shared genetics, stretched taut across a caucus demonstrating decades of difference in opinion, my circuits were short and I sought respite where I shouldn’t. I foolishly attempted to turn my most loving tryst of the last year into a source of relief, as if from the warmth of this old flame I had never been swiftly released. To stay in this place of great love and great pain was a sieve, holding me from the lonesome boil of a pot that could be much hotter. Because what is there to say about death? We live and we die. But heartbreak is a stew that I could stir until I starve.

And in the distraction of my despair, a vulnerable state that I should have protected more intently, I did something that was not only unhelpful to myself, but worse, was a mode of harm that is distinctly unpoetic. I looked at the social media profile of the aforementioned Someone I Should Not Have. She was seemingly guilty of an immense sin: appearing to be happy at a time when I was certainly not. I went down a rabbit hole, rabidly scooping and consuming hot coals of content in desperate delusion until my eyes and insides burned alive. The posts sparked great creative work from my most ungenerous imagination as they both literally and figuratively seemed to jeer: where the grass is greenest is without you. I had been successfully carved and discarded like infected tissue, of which even a scar was farther than a memory.

Like an arrogant child, a victim of my own vanity, I sit and I stew and gag and I grieve at the indignation of my wounded ego. I seek out advice from my friends who, like my aunts, provide support in the administration of their own recycled battle plans. And this is where I stay as, the priests proclaim, my grandfather’s soul takes his chai in the breach between my breaths. I am ashamed. I have never felt sympathetic towards Romeo’s first scene: pining in a darkened room for a past with Rosaline; and my opinion of him may be even less cordial if his pity took the stage at a Montague memorial.

I selfishly lament being so easily forgotten. I am irrational, and need to indulge in moments alone, not yet exhausted by the decades I’ve spent in my own head. Children storm around me with the sound of charging horses. What exactly does it look like to be “healed?” A knock on the door, lunch is ready, time to come down. What do I sacrifice in pursuit of my dreams? Wimbledon is on, the crowd goes wild, I remember how Thatha loved watching tennis. Will joy ever announce itself again? Every bathroom is occupied and there’s no more space in my journal. Will I ever be worthy of a family of my own? Spit out that bite, there’s onion and garlic. What keeps me from the gratitude that others’ so easily express? Time to go play badminton. Was I ever truly loved? Will I ever share a home? Who will reluctantly play badminton and obsess over Wimbledon and be tasked with avoiding the onions and garlic when I die?

For the next few days, I mimicked my grandfather further, and walked like a corpse. I sat in the living room with my family, who are discussing, as is constant this week, the specifications of the religious rites to be performed the next day. They are making sure they have all of Thatha’s historical and astrological information correct, which is to be relayed to the priest the next day. We discuss each others’ Nakshatras, a star each person is apparently assigned through Vedic astrology. It is strangely absent from Co-Star. As we read about the particulars of our loosely shared faith, a devastating realization hits one of my uncles: the home they are about to move into has a door that is facing Southwest.

Madness descends; phone calls are made to priests and realtors, while family members across the house pull out Google Maps to verify what directions their homes are facing. I learn that a Southwest facing door is considered inauspicious, a fact that every landlord I’ve met seems to have left out of their lease. I learn, from HTML websites peer reviewed by the gods themselves, that you are not allowed to sleep with your head facing North. East is best, West is OK, South is not ideal, but North is unacceptable. It’s not like you’ll die, I’m reassured, but if you suffer a stroke earlier in life than is expected, you can’t say that u/guruji_modiluvr111 didn’t warn you. To sleep with your head facing North is reserved for death, so your soul can travel in the correct direction, or something. I recall that cold hour when I sat with Ambi Thatha, holding his ears and measuring his nose for the last time. We faced North, thank gods.

An uncle posits that these rules could be a consequence of the magnetic polarity of the Earth, and I am surprised; I was previously unfamiliar with the geological expertise held by my family of computer scientists and businessmen. My parents muse on which way their beds faced during certain years of their life, and weigh this information against the circumstances of those times. Did their careers develop while their beds pointed Northeast? Was the family happy in our Western facing home? And I scorn this practice in my mind until I start doing the same.

Michigan, K-12: Bed faced North, which is bad, but things were great K-6 then not as good 6-8 then really good 9-12.

Northwestern dorms: Bed faced North; things were good freshman fall then bad in the winter then good in the spring then generally really bad sophomore year.

Evanston apartment: Bed faced East, which is good, and life was pretty good, though that’s when Atharva and Vilasini Athai died and also the pandemic happened which is bad but my writing was good and I got cast a lot and my friendships were great.

West Hollywood apartment: Bed faced South which is not the best and I got fired from two jobs but I made a lot of friends and got signed and fell in love but also got dumped but my auditions were good and my writing got better.

Current LA apartment: Bed faces Southwest, which is bad for a door but not sure if it’s bad for a bed. My grandpa died but I’m on set a lot and my friendships are great and my art is really good.

Conclusion: inconclusive. Need more data points. At least I have not yet suffered a stroke.

That night, I help my grandmother put the dishes away, and she tells me to go outside, because the planet Venus is visible in the sky tonight. I sit outside and I see the planet. I re-download my Sky Guide app, look to the stars, and see that Venus is situated right amongst the constellation Leo, which is just where she was when my sister and I were born.

I mention this to my dad, given his involvement in my birth, and we discuss the practice of astronomy or astrology, of turning our eyes up once the sun travels down. How and why the countless people over countless years have tried to make sense of their lives through the stars. How, when faced with the indignity of heartbreak or helplessness in the face of death, we have seen heavenly bodies streak across the sky and have identified them as gods of love, or rage, or fortune, and prayed that their course show us clarity. When I look to the sky, I feel akin to people who occupied pasts I can only read about and futures I can only imagine; who, like I, feel sometimes that life is so out of our own control. I tell him, in a way I can only hope he understands, as I feel no one ever does, how often I think about this when I sit in the park, and see all the trees that have sprouted from the ground and grown to massive size, and plants that flourish even as their companions wither in the dirt. Knowing now so deeply how we do too. All life is so temporary; we live and we grow and we flourish and wither and die, and while we do, we love other people and places and thus we so constantly grieve the mortal things.

I wish there was a rite I could do or a routine I could follow, a diet I could take that would send away all the losses and answer all the unknowns. I wish that science could tell me who will be there when I die, provide an equation that determines whether a love is true, to know beyond a doubt which direction to lay my head at night to ensure my loved ones are safe.

On the thirteenth day, our official mourning period had ended. We cook a large meal for the priest and one of his friends, and they tell us that Thatha’s soul has officially left our home to travel the stars. The many families who shared this house over the last two weeks prepare to leave. Before we go our separate ways, we spend one last evening together, visiting the river where we spread Thatha’s ashes the week prior.

The air by the Meramec river in East Missouri is hot and sticky. It is the kind of summer evening where your skin is matted with sweat, your arm hairs perked to respond to a bug bite. It’s a steep walk down to the river, but with some support, my grandmother is able to climb down the muddy hill and touch the water. The river is flowing quickly, a fact we had noted while watching Ambi Thatha’s ashes expand into a fluid explosion when they contacted the water one week ago.

I notice a more static stretch of the river a short walk away, and walk over there to skip a rock. The kids and adults quickly notice and follow; because who could resist such intrinsically human fun? My fathers rocks do well in the pond, and we share techniques to achieve a greater number of skips with greater distance between them. My sister and mother and uncles and aunts join in. My little cousins' rocks hit the water and unambiguously, immediately sink, which makes them cry. My grandmother’s rocks do the same and she laughs.

Video by ria.

We drive to a nearby park. My sister and I take to the jungle gym to see if our retired limbs can still overcome the structures. My younger cousins do the same, but with a little more competition fueling their efforts. My aunts and mother unexpectedly find a part of the playscape to make their own as well. The decades separating each pair do little to help distinguish the laughs I hear from different corners of the playground.

One could say that they twirled.

The next day, our family drives back to Georgia. My grandmother calls to tell us where she has re-planted all the flora we were given in the weeks after Thatha passed away. My father refers to the pictures as “flourishing new growth.” I look out the window and see nothing but the lush greenery of middle America in the summertime. Poking through a small excerpt of this jungle is the bright crimson and yellow of a McDonalds sign, and I laugh at the sight of something that is, for once, so undeniably certain.

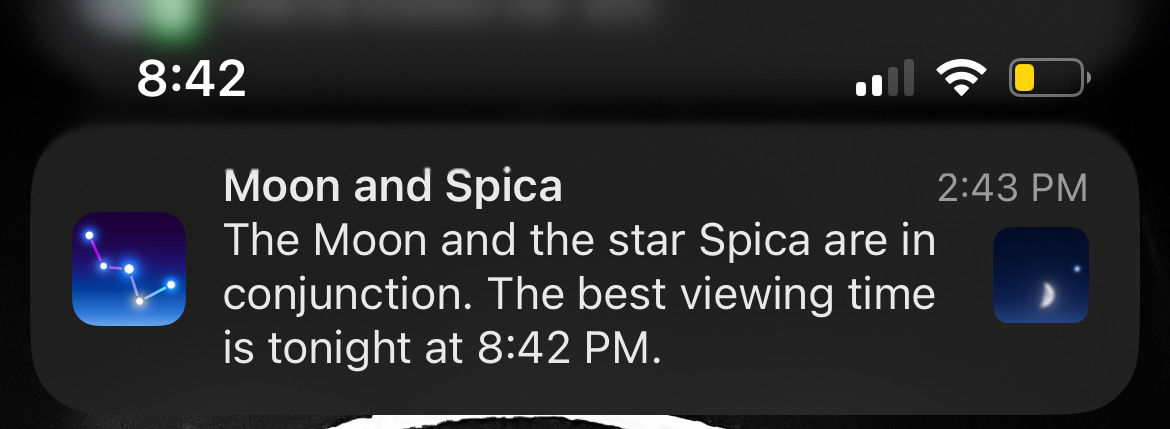

A few evenings after my return to LA, I get a notification from my Sky Guide app that the star ‘Spica,’ part of the constellation Virgo, is conjunct to the moon at just this moment, 8:42 PM. I venture to my front lawn and sit back, gazing at the celestial objects. My first love was space. The first thing I ever wanted to “be” was an astronaut. I mourned that dream long ago, and I have mourned many other dreams since. Although I might never walk amongst the stars, I know what it is to feel weightless. To be carried an inch higher in the air by something I might sometimes call love. Maybe someday, my grandchildren will write of their artist grandfather with the soul of an astronaut.

The death of my grandfather raised every great question I could ask. I reflected on his life, and how it trickled and flourished within generations, and therefore outlived him. I wondered about the lives that will surround me when my time comes to pass. I distracted myself with reflection on past love, as if to see her moving on was to watch as I ceased to be mourned. I wondered whether I was unworthy, in many senses, of having a home. Ultimately, all these questions are the same. They ask, whether the lens be metaphysical or romantic or financial: What is the value of my life?

I attribute many of the questions I ask about my own future to the stories our empire tells us of the dreary fates that artists deserve. But somehow, gazing at the moon placed against a corner of Virgo, I become aware of a fact: I am driven by an immense sense of purpose. I know that isn’t everything, but I’m certain that it’s something.

After Thatha’s funeral, I wrote in his journal a poem I was shown at the start of the summer, one that I’ve quoted in this newsletter before. The last line of the poem instructs to, “When the time comes to let it go, to let it go.” I’m not sure if that time has come, or if it ever will. My love, in general, feels inevitable, as if it were imposed by the stars.

Thank you for reading Part 3.

Rest in peace, Ambi Thatha.

It’s been an honor to read this series and learn about your grandfather. You captured so many complex/competing(?) emotions so well. Sending well wishes & prayers to you & your family!