Rest in peace to my grandfather, Ullanurmadom Ramasubramanian Harihara Subramanian, a name I have only used one time, to get his medication from an overwhelmed CVS pharmacist in Chesterfield, Missouri.

We called him “Ambi Thatha” for short, but mostly just “Thatha,” since it means grandfather, and there was no need to differentiate given that my paternal grandfather passed away before I was born.

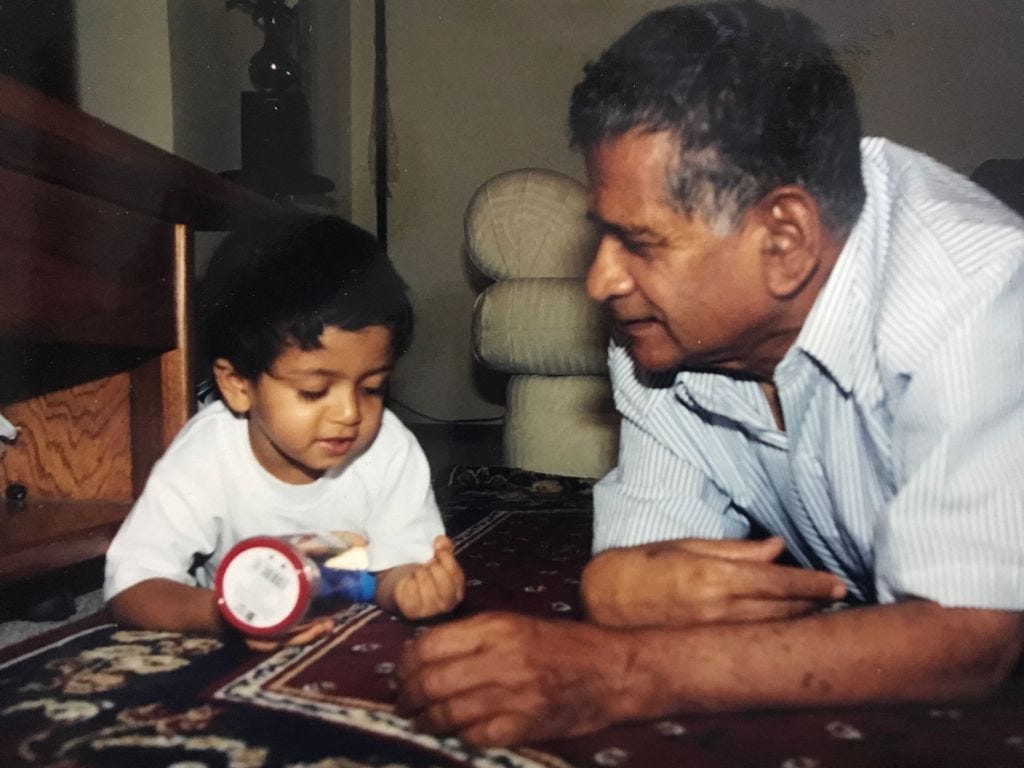

He was the only grandfather I ever knew, and he was perfect. He was defined by a set of characteristics that remained constant over the 24 years that I knew him. He was mostly quiet, but had a sharp, crass sense of humor. He was extremely silly. Growing up, he taught my sister and I tons of little tricks that we took to the school’s playground and hallways: a magical method of slapping your arms to create music; an optical illusion performed with your hands that when your friends try to repeat, ties them up in knots; a malicious prank placing your thumb against your pointer finger and asking to measure someone’s nose, only to pinch them upon contact. Silly, annoying, perfect grandfather tricks.

He was an engineer, and more than an occupation, this was an identity of his that coursed through his body and affected his world. He was constantly, quietly, building contraptions to help the people around him. When I was a child and couldn’t reach the cord that controlled my ceiling fan, he fashioned a pulley with my Spiderman toy as the handle to help me reach it. In the house in Missouri where he spent his last years, he built a retractable bird feeder that could be brought closer or farther from the deck, so the birds could eat without, as he would put it, shitting on the wood.

He was extremely precise, and mathematical. He stayed sharp. He played sudoku and journaled daily, noting things like the weather, the activities of others in the house, and whether or not he took a shower. He basically always showered; that was very important to him. He was a well groomed, hygienic man with a full head of aggressively back-combed hair, something the men of my family envied and I hope has passed down to me. His journals rarely noted his emotional state, besides in the last year of his life, when he would occasionally note where and how strongly he felt pain.

He was not an ambitious nor egotistical person. His nature was to self deprecate, and he did not seek fulfillment from his work. One story, as commonly repeated as every story in a family becomes, was about how Thatha would sit on the construction site and draw caricatures of the people he worked with. He was a gifted cartoonist, but reserved his skills. My aunt told me that she constantly begged for him to draw her, but for the most part he refused to draw family members. None of us are quite sure why. Towards the end of his life, my mother asked him if he wished he could have been an illustrator instead of an engineer. He always said that he had no other option but to become an engineer, and that he wasn’t smart enough to do anything else. But I don’t believe he had the desire or the ambition to live as an artist either. I think he just loved to tinker. As I knew him, he had the soul of an engineer just as much as he had the soul of a cartoonist.

His first language was Tamil, but he mostly grew up in Kerala, so he was also fluent in Malayalam. He spoke both of these languages much more comfortably than English. He was also a bit hard of hearing. As a child, I spoke incredibly fast all the time, only proficient in English. Every time we saw our grandparents, I would be instructed by my mother to speak slowly, loudly, and enunciate, and I was horrible at all of it. I will forever harbor guilt at not committing myself to learning Tamil at a young age.

When I was a preteen and I visited my grandparents in India, once a week, I would take the newspaper, flip to the weekly comics section, and devour the selections with breakfast. I don’t think we got the newspaper back home in Michigan, and the “funny pages” is an American tradition that has long been dead and gone anyway. The next time I visited India, as a teenager, Thatha presented me with a poly-string folder of all the cartoons from the paper that I had missed over the years. He had clipped the comic sections out of the newspaper every week that they arrived for four years, and collected them in a folder for me.

My parents moved homes a few times in the years afterwards, and I have obsessively torn apart each house looking for the folder. I have not been able to find it, and it remains a great tragedy of my life to be unsure of its whereabouts. If life was a fairytale (a la a Disney Channel Original Movie), I would’ve found this folder before he passed and indulged in the opportunity to sit at his bedside, going through the comics and reminiscing with him. But a lesson I relearn, it feels like every day, is that fairytales are fairytales and life remains something different.

He and I found each other through cartoons. In December of 2019, while at home over break, I began to draw caricatures. I practiced by drawing hundreds of people I knew over the course of a few weeks.

I continued a drawing practice, and at the end of college, in June of 2021, I visited my family in Missouri. Thatha and I sat together and exchanged a notebook back and forth, passing new drawings to each other.

The inability to communicate verbally presented a barrier in our relationship to one another for most of my life. But the silly tricks, simple jokes, and the gestures to and fro in the creation of a helpful tool or a presentation of newspaper clippings, allowed us to relish in a lifetime of memories together while hardly exchanging many words. All of his knowledge, every language he spoke and skill he practiced, was primarily wielded towards the noble goal of spreading a smile to someone he loved.

In the fall of 2021, my mother is in India with her parents, helping them get their affairs in order after they had remained in the United States for longer than expected due to COVID-19. On this trip, my grandfather’s recurring cough begins to draw up blood, the cause of which is swiftly identified as lung cancer. They decide to begin treatment in the United States, where all of his children are, and where it is assumed he could receive a slightly improved standard of care. This is the same course of action taken by the family of my friend Atharva in 2019, who was in India when he experienced the first symptoms of the Leukemia that took his life merely three weeks later. It is a different course of action than was taken by Vilasini Athai, my father’s eldest sister, who passed away in 2020 after 7 months of treatment for pancreatic cancer. One hard thing about cancer treatment I’ve learned over time is how impossible it feels to make any right call, and how easy it seems it is to choose from a myriad of imperfect decisions. C’est la vie.

It is the winter of 2021, and my father has just picked me up from the airport in Missouri, where Thatha has been in the throes of cancer treatment. On the way to the house, my father informs me that last night, Thatha had gone through an “aspiration event,” basically meaning that he choked on a drink and now had an obstruction in his airway. This complication is life threatening, and I steel myself for the possibility of losing my grandfather this weekend.

He ends up being okay. When it is appropriate, I visit him in the hospital with my aunt, and there is something new in the gaze we share. I sit with him, reading a movie script, and talk to him about my ambitions. After four years of voice classes at theatre school, and a pandemic that forced me to take up a meditation routine, I finally understand how to speak to him slowly, intentionally, and deliberately. The time we spend together feels more precious.

After that near-death surgery, Thatha started expressing affection towards us in a completely new way. On the ride back from the hospital, my aunt mentioned that she had never seen him hug or hold hands the way he began doing. When we returned home, I saw him lunge towards his grandchildren, hugging them desperately close. A sense of horror seemed to grab the back of my skull.

For the two years before this incident, I had lost a loved one each summer. I became a person who thought a lot about death. I had decided for myself that death was natural, and not something to fear. I figured if one was lucky enough to live to old age, to have children and grandchildren, death would seem trivial, almost a relief. But seeing my grandfather clutching his family with all of his scarce, precious strength, I realized that he was eighty-four years old and did not want to leave. He wanted every second he could get. The realization that life may always feel valuable, ironically, devastates me.

Whenever my sister and I are home, we go through our family’s many photo albums. Usually we go through our photos from childhood and reminisce with our parents. As I’ve gotten older, I’ve started studying the old pictures of my parents, aunts and uncles, looking for the genetic hints that could paint me an image of what my future will look like. Although I know that when it comes to genetics, you basically get a random combination of information from your parents and thus their parents, it always felt like I was built out of more than just one fourth of my Ambi Thatha. He was a bit small and wiry, and now seems to hide in the crinkles around my eyes when I smile. Our family always poked fun at the way he clasped his hands behind his back and paced. Well before I got old or wise enough to be as contemplative, I started doing the same.

Nature v. Nurture, Chicken v. Egg, it’s impossible to say to what extent I’ve made an effort to grow into my Thatha’s image. In any case, it has felt inevitable to hold him in the extra notch on my wristwatches, to see him editing my journal entries and guiding the pen as I draw my cartoons. I pray to god that his spirit is now watching over my hairline.

In his last days, when his sense of the world and those around him was slipping away, my father asked him if he could remember my father’s name, specifically asking, “Who am I?” Thatha, at this point hardly able to speak, let alone recollect information about those around him, replied, “A very fine gentleman.”

It’s daunting to think about what our core attributes really are. In my grandfather’s case, when stripped of his faculties and memory, as close as he could be to his essential spirit, with the same scarce strength that he used to hug his grandchildren, he responded to my father with a joke. Maybe his soul was that of a cartoonist after all. Whatever his soul was, it was perfect.

One newsletter can’t do him justice, so I have more coming in a second part. To those still reading, I truly appreciate you sticking around to hear about someone else’s grandfather. I don’t expect anyone else’s precious time to revolve around my life experiences, but I feel compelled to demonstrate that Ambi Thatha was a large planet in my orbit. He drew my tides towards drawing and writing and witty one liners, and in turn has been as indirectly responsible for saving my life as he is for creating it.